Artiklar från 2008 – till idag

Photography: courtesy of Ahmad Joudeh.

“Dance is my passport and because of dance, I am alive”

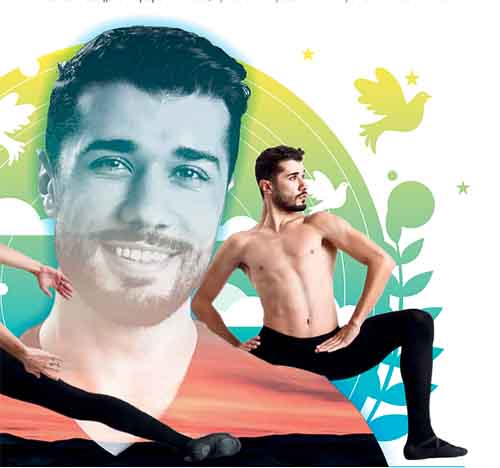

AMSTERDAM: Maggie Foyer meets the Palestinian dancer Ahmad Joudeh, now resident in Amsterdam.

Few dancers at the beginning of their professional career have been as fêted as Ahmad Joudeh, the Syrian-born, Palestinian dancer. When we met in Amsterdam at the Muziektheater, home of Dutch National Ballet, he had just returned from Paris and a dinner date with President Macron.

Photography: courtesy of Ahmad Joudeh.

Conversely, few dancers have had as traumatic and dangerous a path to reach professional status. Born in 1990 in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus, he was on the frontline as the Syrian civil war raged around him.

In a culture that saw dance as only for women, and even then, viewed with suspicion, he faced fierce societal opposition and his father’s anger.

That he has achieved so much is a tribute to his tenacity, talent and great passion for dance.

The struggle to be a dancer, especially for boys, is well documented, but Ahmad believes that dance found him. His father was a musician and taught him to sing as a child.

At the age of eight, he performed at a school festival and saw a group of little girls dancing ballet to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.

“It was very basic, but I wanted to dance like them. I believe dance is for everyone – not just girls. Swan Lake is famous in Syria, like everywhere, so I found the music and tried to teach myself but I had to keep it secret from my father.”

At 16, and self-taught, he auditioned for the Enana Dance Theatre in Damascus. “I think they liked me because I was tall”, he said. The Russian ballet mistress, Albina Belova, recognised his potential and while performing with the company he received formal training in ballet.

At 19 he was able to enrol at the Higher Institute for Dramatic Arts. All the while he faced his father’s disapproval and one beating was so severe his leg was nearly broken. “A man dancing ballet is the worst thing in the Arab world.”

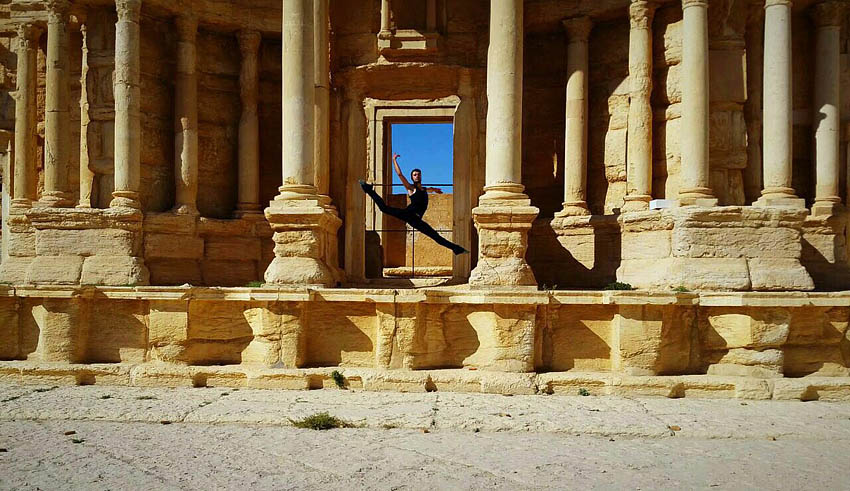

When the family moved to the relative safety of Palmyra, he stayed on in Damascus living for two months in a tent on the roof of a damaged building to continue his studies.

He was rewarded by graduating as the top dance student in his year.

While studying, he continued to dance with Enana, touring throughout the Arab world. It was the Arab version of So You Think You Can Dance in 2014 that brought him to public notice, gave him family approval and changed his life.

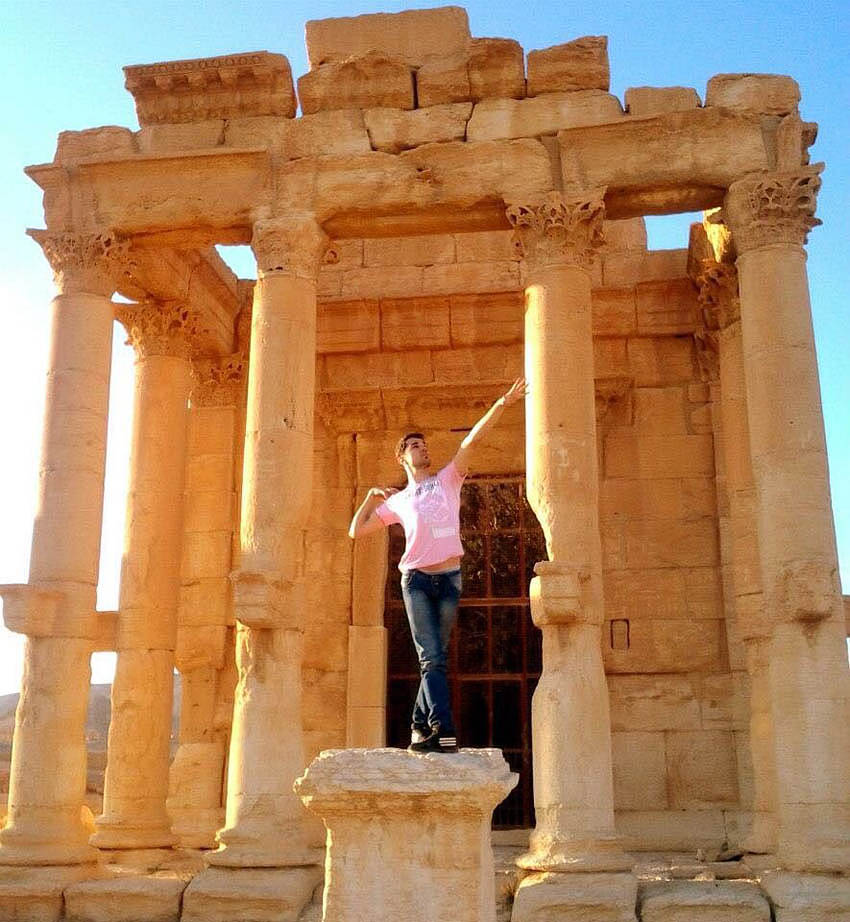

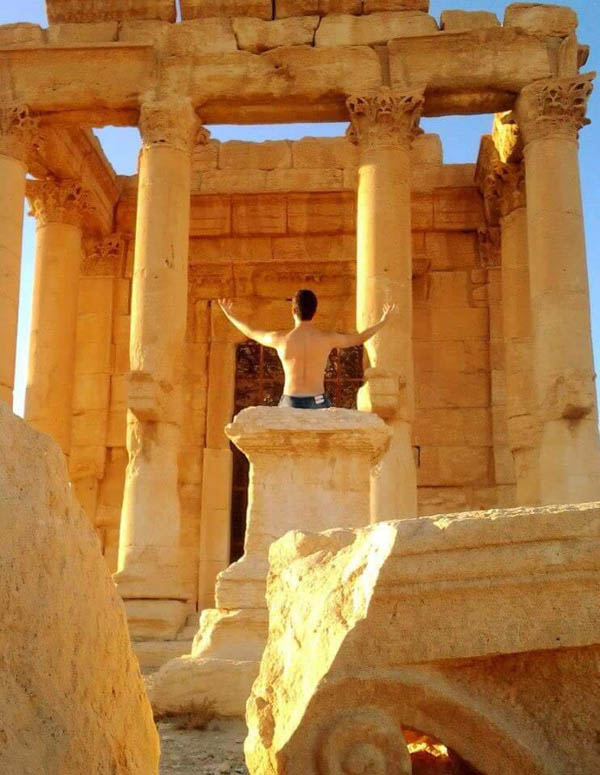

Dutch journalist, Roozbeh Kaboly, saw Joudeh’s photograph on Facebook and went to Damascus to film him dancing in the ruins of Palmyra – a highly dangerous venture for both of them.

However, nothing would prevent Ahmad from dancing. He has a tattoo on his neck that says: “Dance or Die”. He reckoned that if ISIS captured him they would see his defiant message if they chose to behead him.

The video was viewed by millions across the globe on YouTube after it was screened first on television in The Netherlands. Ted Brandsen, director of Dutch National Ballet, saw it and was captivated by this dancer who showed such total commitment. He set up a fund that raised €25,000 to bring Ahmad to Amsterdam on a study visa.

Photography: courtesy of Ahmad Joudeh.

A specially designed programme introduced him to jazz and hip hop in addition to his ballet and contemporary classes at the High School of Performing Art, and he is now concentrating on choreography, performing and teaching.

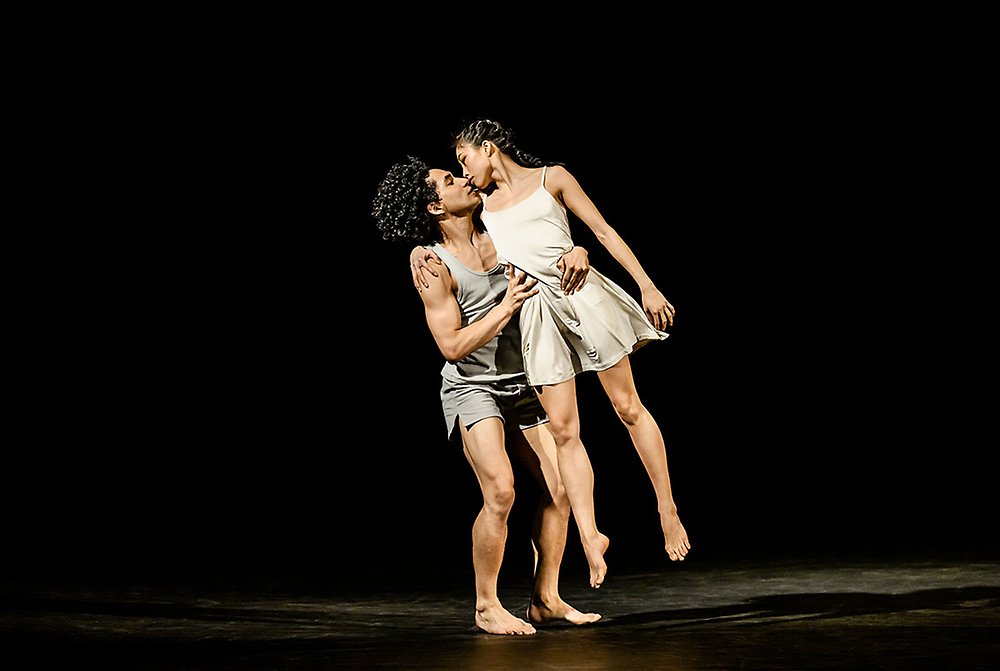

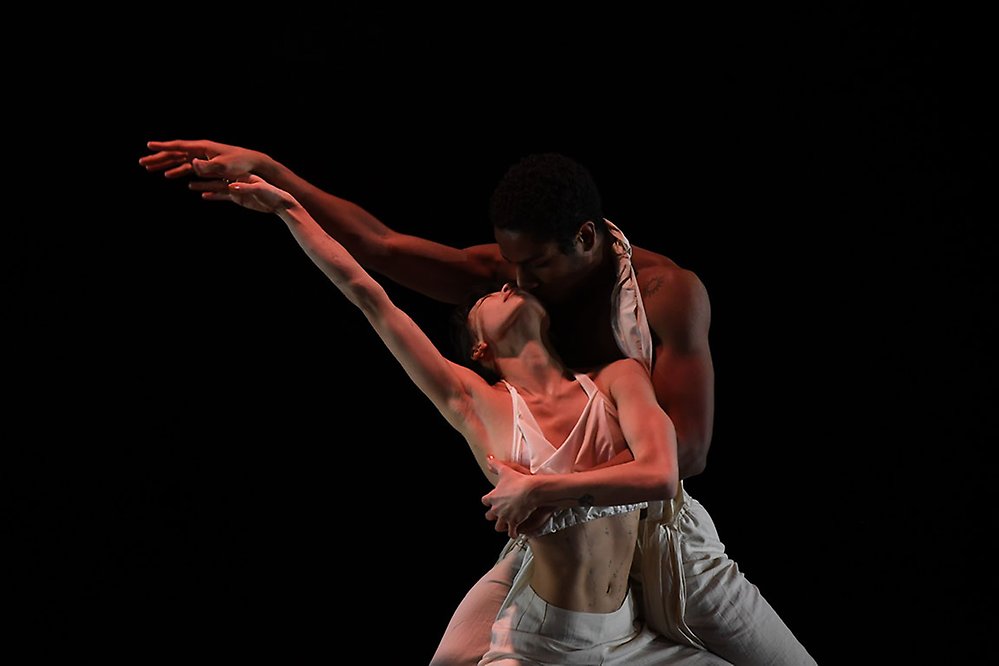

While his classical technique is not at company standard, Ahmad has been embraced by the dancers, joining in classes, making many friends and performing character roles in Coppélia and The Sleeping Beauty.

He has had great success with his own choreography, performing to an audience of 14,000 at Amsterdam’s largest venue, the Ziggo Dome, in addition to invitations to dance in festivals in major European cities.

His passion for dance extends to teaching. Previously in the Yarmouk camp Ahmad taught dance to children, including those with learning difficulties. He spoke with great fondness of his young pupils and the latent artistic talent in Syria. His hope is that the fund will also help these artists.

In Amsterdam he continues his children’s classes in addition to ballet classes for amateurs based on the philosophy: “You don’t need to punish yourself in the ballet class, enjoy it and fly. The joy of dance is more than the technique”. Working on ideas he formulated in Lebanon, he now directs workshops for refugee children, based on his experience with dance and how it can heal by releasing emotions through movement.

Ahmad believes that dance must come from the soul if it is to move people and through dance he can be a messenger for his people.

His invitation from the French President came about because of the huge publicity surrounding his performance in front of the Eiffel Tower. “A Syrian singer, Sanga, took my words from the documentary and made a song and I arranged a dance to it.”

Ahmad recounted to me his emotion when dancing to the phrase, “I was free in the jail” which had forced him to interrupt his rehearsal. “It took me back directly to the moment I had said it and it hurt so much, I couldn’t breathe.”

He pauses for a long time.

“It is hell there. My mother, my brother and my sister are still in the house on the frontline. They have been attacked twice because of my publicity and they only survive by chance. I can help them financially, but I cannot protect them.”

Ahmad Joudeh inhabits a world that is part dream, part nightmare. As all the doors to dance success open, he is still stateless.

With no passport, he can only travel when he has an invitation and a visa, “but, when they see my papers at the airport they make me wait. They check my travel documents many times for no reason. There is no respect for humanity in treating people according to their documents.”

Photo Tiberiu Capudean

When I asked him what was best about Amsterdam the answer came directly: “Freedom. I can walk from

the gym to the studio in my training clothes and nobody judges me. I like the very direct way the Dutch deal with people. It makes things very easy.”

However, his independent spirit struggles with the system that tries to classify him as a refugee. “I’m a dancer. Dance is my passport and because of dance, I am alive.” He has bold ambitions for the future: “I want to direct the Syrian National Ballet, with Syrian dancers in a peaceful Syria.”

Ahmad is now, thankfully, reconciled with his father. “He is so proud of me now. He said the night he beat me, he came home angry with people taunting him about his son, the dancer, and then he found make-up in my bag.

On my last visit, he started to dance with me, doing some of the moves he had seen in my video. I started to cry and had to run and hide in the toilet.

You need to let the burden of hate go or you will never find peace with yourself. Eleven years without talking to me, or even looking at me because I was something shameful – and now he is dancing.

Photography: courtesy of Ahmad Joudeh.

He is an artist, like my brother, so for me it was really strange that he was against dance. “In my way of thinking, if you are not man enough on stage, you are not beautiful. The beauty of a pas de deux is when the woman is enjoying her femininity and the man, even if he is gay, is a real man.

So, that is what you enjoy to see and there is nothing to be ashamed of. Whatever your personal life is – keep it in bed!”

Ahmad’s story has similarities with Billy Elliot, but with the added danger of bombs, gunfire and sudden death possible at every street corner. At the heart of each story is the passion of a young man and the healing power of dance.

For further information on Ahmad Joudeh, visit danceforpeace.nl/english.

This article was first published by Dancing Times, and Dansportalen has been approved to publish it.

https://www.dancing-times.co.uk/ Länk till annan webbplats.

Länk till annan webbplats.

Maggie Foyer

10 Sep 2018

-

Gustavia – berättelsen om Sveriges okände prins

Nyskriven balett om Gustav Badin och hans uppväxt vid hovet, i koreografi av Pär Isberg och regi av Amir Chamdin. Urpremiär på Kungliga Operan s stora scen den 18 oktober....

-

Yoann Bourgeois tillbaka till Göteborgsoperans Danskompani med ett sant styrkeprov

Efter fyra år är det dags igen för den franske koreografen Yoann Bourgeois att återvända till Göteborgsoperans danskompani. Denna gång för verket We loved each other so m...

-

Spot on Darrion Sellman – dancing the leading role Siegfried in Swan Lake

In August last year Darrion Sellman arrived to Stockholm and joined the company. Darrion says: “It has been a change to come to Stockholm. A vibrant city, small but calme...

-

Kalle Wigle nyutnämnd solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin

Dansportalen gratulerar svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle som nyligen utnämnts till solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin.

-

Succéduo skapar nytt efter segertåg i Sverige och Europa

Intervju Hugo Therkelson och Tobias Ulfvebrand

-

40 år senare: En dansares triumf över tidens utmaningar

Förra sommaren ringde telefonen hemma hos Heléne i Kungsbacka. I lördags den 16 mars gjorde hon comeback på scenen efter nära fyra decenniers frånvaro och dessutom debut ...

-

Fart och kunnande på Pro Dance Galan 2024

Gamla operabyggnaden vid Bulevarden är ett Dansens Hus även om ett nyare Dansens Hus numera finns i Helsingfors, det också i centrum. Båda har sin publik, och båda behövs...

-

Svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle har stora framgångar i Berlin

Kalle Wigle är utbildad vid Kungliga Svenska Balettskolan och vid Royal Ballet School i London. Han fick anställning vid Operan i Stockholm 2016. Från hösten 2023 är han ...

-

Timulak/Portner två olika verk men med flera beröringspunkter

Från och med 9 februari och nästan en månad framåt dansar Kungliga Operan i Stockholm Totality in parts av Lukás Timulak och Bathtub Ballet av Emma Portner . De båda koreo...

-

På jakt efter det fullkomliga: nationens skickligaste dansare och – smultron!

Balettpedagogernas förbund ordnar vartannat år i Finland en nationell balettävling, i år 20-21 januari. Ett råd av balettkonstnärer med bakgrund som meriterade dansare ha...

-

Young Choreographers en föreställning där dansare från Kungliga Operan koreograferar

Tisdagskväll på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm och det är premiär för Young Choreographers. Dansare från ensemblen får chansen att pröva egna idéer och koreografera sina kol...

-

Operans VD Fredrik Lindgren: På sikt vore det fantastiskt att få ett nytt Operahus i Stockholm

Kungliga Operan är en 250-årig kulturinstitution i hjärtat av Stockholm. Över 500 anställda levererar hyllade föreställningar med utsålda hus. Dansportalen har samtalat m...

-

Från Svenska balettskolan i Göteborg till ungerska Statsoperan i Budapest

Det började med 6 år på Svenska balettskolan i Göteborg med start i årskurs fyra för Mattheus Bäckström och Auguste Marmus . Mattheus gick ut 2017 och hade då blivit antag...

-

Joseph Sturdys verk Lucid Episode inleder nyårsgalan på Kungliga Operan

Vi befinner oss på Kungliga Operan. Det pågår repetition med två dansare som är med i Joseph Sturdy s verk Lucid Episode som inleder själva nyårsgalan den 31 december.

-

Göteborgsoperan sjunger in julen med En Julsaga

Göteborgsoperan avslutar december månad med nypremiär på musikalversionen av Dickens En julsaga . Föreställningen är breddad med humor och medmänsklighet. Adams julsång bl...

-

Nötknäpparen, nypremiär på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm efter fyra års uppehåll

Det är nypremiär av Pär Isbergs Nötknäpparen på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm. I salongen sprids julstämningen och publiken får vara med om en dansant och virvlande berätte...

-

Giovanni Bucchieri – en konstnärlig kameleont

Det är premiär för filmen 100 ÅRSTIDER . Upphovsmannen har gått från dansare till multikonstnär. Möt regissören Giovanni Bucchieri i en personlig intervju med Dansportalen...

-

”Mycket talar för att vi inte kommer att kunna vara kvar där vi är nu,” säger Hans Lindholm Öjmyr, ny chef för Dansmuseet

Hans Lindholm Öjmyr är filosofie doktor i konstvetenskap och har skrivit en avhandling om scenografi på 1800-talet vid Kungliga Teatern/Operan. Hans har tidigare varit av...

-

In a heartbeat, ny världspremiär på Göteborgsoperan

In a heartbeat bekrivs som ett pulserande dansbubbel och på Göteborgsoperan är det nu världspremiär allhelgonaafton på stora scenen för Hofesh Shechter s verk Wild poetry ...

-

Le Corsaire, svensk premiär på Kungliga Operan med virtuos dans och teknisk skicklighet

När Kungliga Operan för första gången ger Le Corsaire bjuds det på en dansfest. Verket som hade sin urpremiär på Parisoperan 1856 kommer till liv och publiken får möjligh...

-

New talents join the Royal Swedish Ballet

Eleven young dancers join the Royal Swedish Ballet company this season. We are thrilled to see them on stage! On October 27, this season's grand premiere of Le Corsaire w...

-

Där låg onekligen ett skimmer över Gustavs dagar

I Livrustkammarens visas den största satsningen på flera år på en tillfällig utställning i samarbete med Kungliga Operan – öppnas 20 oktober, Teaterkungen: Prakten, makte...

-

Attityder som uppskattades

I Drottningholmsteaterns déjeunersalong gavs i september in innehållsrik, högklassig presentation av ett forskningsprojekt som genomförs på Kungliga Musikhögskolan och fi...

-

Spot-on Kentaro Mitsumori, dancer with the Royal Swedish Ballet

Kentaro Mitsumori has been a member of the Royal Swedish Ballet since 2017. We have seen him in many roles, in Swan Lake, Cinderella, Don Quijote, The theme and variation...

-

Kalle Wigle-Andersson får stipendium från Jubelfonden

Kalle Wigle-Andersson: Jag är utbildad och diplomerad vid Royal Ballet Upper School, London 2016. Innan dess gick jag på Kungliga Svenska Balettskolan 2006-2014. Sedan mi...

-

Wicked, musikalen om häxorna i Oz

Göteborgsoperan inleder sin höstsäsong med den mytomspunna succémusikalen Wicked. Exakt tjugo år efter Broadwaypremiären 2003, sätts den nu upp för första gången i Sverige.

-

Balettgalan i Villmanstrand är sensommarens succéevenemang

Balettgalan i Villmanstrand vid Finlands östra gräns gavs i år för 12:e gången och var igen en succé med både nationella och internationella dansare. Galans grundare och eldsjäl Juhani Teräsvuori hade...

-

Möte med Fredrik Benke Rydman om ”The One”

Det är mannen från dansgruppen Bounce, koreograf till egna versioner av Svansjön och Snövit bland mycket annat. Jag träffar Fredrik Benke Rydman på en liten thaikrog mellan repetitionspassen.

-

“A new look at it” – Lady MacMillan about Manon with the Royal Swedish Ballet

As part of the 250-year jubilee program of the Royal Swedish Opera and as a tribute to the long-lasting cooperation between the Royal Swedish Ballet and world-renowned English choreographer Sir Kennet...

-

Urpremiär av episkt dansverk på Norrlandsoperan

Den 1 september bjuder Norrlandsoperan på säsongsuppstart för dans med urpremiär av den episka föreställningen Remachine signerad koreografen Jefta van Dinther . Ljus, ljud, röst, koreografi och scenog...

-

Contemporary dance av Hofesh Shechter på GöteborgsOperan

Danskväll med intensiv klubbfeeling, smittande glädje och en upplevelse som börjar redan utanför operahuset.

-

Julia Bengtsson – internationell barockdansös från Sverige

Höjdpunkten under årets förnämliga Opera- och musikfestival på Confidencen var iscensättningen av Jean-Philippe Rameaus opera Dardanus . I en annan föreställning, A Baroque Catwalk , gjorde Julia Bengts...

-

The Royal Ballet School Delights

Written on the faces of the dancers as they spin and leap in the ecstatic final moments of the Grand Défilé , is the smile that says, ‘I did it’. It’s what I look forward to year after year and it neve...

-

Ett barockt spectacle på Confidencen

Confidencen Opera & Music Festival inleds den 27 juli med Jean-Philippe Rameaus mästerverk Dardanus, som genom ett gediget arbete får sin nordiska premiär på Sveriges äldsta rokokoteater – 284 år efte...

-

Möt Vivian Assal Koohnavard dansare vid Staatsballett Berlin och aktivist

I Berlin träffade jag och arbetade med Vivian Assal Koohnavard. Vivian fick sin dansarutbildning i Sverige och Tyskland. Hon har varit anställd vid Berlin Staatsballett sedan 2018. Där deltar hon i de...

-

Peter Bohlin om Kungliga Svenska Balettskolans uppvisningsföreställningar

Skolårets sista föreställningar på KSB var uppdelade i fyra program. Några koreografier var storartade, andra inte. Här, mot slutet, ett försök att resonera om anledningar till detta.

-

Dans i Stockholm Early Music Festival

I 2023 års version av Stockholm Early Music Festival , den tjugoandra i ordningen, ingick två dansföreställningar. I fablernas värld , en kort musikalisk och dansant barockföreställning med Folke Danste...

-

.jpg)

Suite en Blanc av Estoniabaletten med fina danssolister

Jag hade möjligheten att två gånger se en ny balettafton med två verk. Black/White innehöll “Open Door ” av polskan Katarzyna Kozielska och Serge Lifars kända och genuina Suite en Blanc . Den sistnämnda...

-

Marie Larsson Sturdy Carina Ari Medaljör 2023

På Carina Ari-dagen 30 maj tilldelades Marie Larsson Sturdy Carina Ari-medaljen för hennes mångåriga och engagerade insatser inom Dans i Nord – en vital verksamhet som under mer än 20 år har främjat m...

-

Manon: An evening to treasure

Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon created in 1974, continues to weave its magic providing a slew of dramatic roles against a volatile and violent backdrop. The Royal Swedish Ballet first presented the ballet ...

-

Instudering av Mats Eks ”En slags” med Staatsballett Berlin

I april 2022 reser Koreografen Mats Ek och jag till Berlin för att hålla audition med dansarna vid Staatsballett Berlin på Deutsche Oper. Vi ska välja dansare till verket ”En slags” av Mats Ek. Premiä...

-

Marianne Mörck berättar sagan om Peter Pan med Svenska Balettskolan

Till vårens uppsättning av Peter Pan och Wendy på Lorensbergsteatern är en av gästartisterna ingen mindre än Marianne Mörck . Efter första repetitionen tillsammans med baletteleverna på svenska baletts...

-

Det var en gång på Grand Hôtel, musikalen som återupptäckts

Göteborgsoperan avslutar sin vårsäsong med premiär den 22 april på Paul Abrahams musikal Det var en gång på Grand Hôtel. Musikalen som legat gömd fram till 2017. En föreställning fylld av dans och mus...

-

Virpi Pahkinen: "Precision möter osäkerhet, matematik möter mystik"

Change – den nya dansföreställningen av och med Virpi Pahkinen – är uppbyggd enligt principen 5 + 5 + 5, dvs koreografi/ljus/musik. Strax före fredagskvällens premiär på Kulturhuset Stadsteatern fick ...

-

För dansens skull dansas Pro Dance galan

Den anrika Aleksandersteatern fylldes åter av dansfolket som ville stödja dansen och dess utövare via föreningen Pro Dance med att köpa biljetter till den årliga galaföreställningen. Artisterna uppträ...

-

Anthony Lomuljo – om hur det är att igen dansa Romeo – 10 år senare

10 år har gått sedan urpremiären av Mats Eks Julia & Romeo på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm. Då liksom nu dansar Anthony Lomuljo rollen som Romeo. När Dansportalen några dagar innan premiären träffar An...

-

Hur bygger vi upp oss själva igen när allt är förstört–Johan Inger om Dust and Disquiet på Göteborgsoperan

Danskvällen Touched visar två världspremiärer på Göteborgsoperan, Dust and Disquiet av Johan Inger och To Kingdom Come av det nederländska syskonparet Imre och Marne Van Opstal . Naturkatastrofer runt ...

-

Mats Ek om Mats Eks Julia & Romeo

Operans Balettklubb gästades lördag 25 mars av koreografen Mats Ek och dansare inför nypremiären av ”Julia & Romeo” på Kungliga Operan. Verket uppfördes på teatern för första gången 2013. Det har ocks...

-

Nordens största danstävling lockade 44 dansare

Äntligen! Det är vad de flesta kände när tävlingen Prix du Nord genomfördes på Kronhuset i Göteborg.

-

Young choreographers en bra plattform för nya idéer

En alldeles särskild glädje med workshopartade föreställningar är att man får se dansarna på riktigt nära håll. Så var fallet på Operans Rotunda 16 och 18 mars, i ett program med sju koreografer och 3...

-

%20Agathe%20Poupeney%20OnP%20-BONP-D%C3%A9fil%C3%A9.jpg)

Gala till minne av den lysande dansaren Patrick Dupond

Under februari var det tre utsålda galor på Palais Garnier i Paris, till minne av dansaren och balettchefen Patrick Dupond . För programmet på galan, se nedan!

-

Madeleine Onne: Man får slåss för sin konstart

Madeleine Onne har varit balettchef i Stockholm, Hongkong och Helsingfors. Dansportalen har pratat med Madeleine om bland annat tiden i Hongkong, Helsingfors och om Stockholm 59°North. Men på vår förs...

-

Triple Bill at the Ballet. What's not to Like?

The feel-good factor was in abundance at the Royal Opera House in Stockholm with a triple bill to send the audience home with a smile.

-

Elever från Kungliga Svenska balettskolan tävlade i årets Prix de Lausanne

Sveriges kandidater i Prix de Lausanne kommer båda två ifrån Kungliga Svenska balettskolan. Theodor Bimer och Alexander Mockrish. Tävlingen firar 50 årsjubileum lite sent då pandemin stoppat ett flert...

-

.jpg)

12 songs + Ane Brun och Kenneth Kvarnström på Göteborgsoperan

Första helgen i februari är det premiär för 12 songs + på Göteborgsoperan. Ett scenkonstverk skapat genom samarbete mellan 18 dansare och en av Nordens främsta koreografer, Kenneth Kvarnström, i något...

Notiser

- Den andra halvan av drömmen – måndag 29 april kl. 19.00

- Nu finns en danskalender på Dansportalen

- Nytt regionalt center för dans byggs i Mölndal

- Kungliga Operan stänger i fem år från juli 2026

- Premiärdansaren Frans Valkama har tilldelats Edvard Fazer pris av Suomen Kulttuurirahasto (The Finnish Cultural Foundation)

- Kulturnatt Stockholm

FÖLJ OSS PÅ

-

Kreativ lyskraft hos GöteborgsOperans Danskompani

GöteborgsOperans danssäsong 2024/2025 blir en virtuos upplevelse med kreativ briljans. Strålkastarljuset riktas mot starka kvinnliga röster och det blir både raffinerade ...

-

Dansarna berör på djupet med sin dansade kyss

Sommaren 2022 turnerade Don't, Kiss .Skånes utomhus i Skåne och Köpenhamn. 23 mars 2024 får föreställningen nypremiär på Skånes Dansteater, denna gång som inomhusverk med...

-

Yoann Bourgeois tillbaka till Göteborgsoperans Danskompani med ett sant styrkeprov

Efter fyra år är det dags igen för den franske koreografen Yoann Bourgeois att återvända till Göteborgsoperans danskompani. Denna gång för verket We loved each other so m...

-

Spot on Darrion Sellman – dancing the leading role Siegfried in Swan Lake

In August last year Darrion Sellman arrived to Stockholm and joined the company. Darrion says: “It has been a change to come to Stockholm. A vibrant city, small but calme...

-

Kalle Wigle nyutnämnd solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin

Dansportalen gratulerar svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle som nyligen utnämnts till solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin.

-

Succéduo skapar nytt efter segertåg i Sverige och Europa

Intervju Hugo Therkelson och Tobias Ulfvebrand

ANNONS

Ur Dansportalens arkiv

-

Nurejevs Svansjön på Stockholmsoperan – en version aldrig tidigare spelad i Sverige

Inför Kungliga Balettens premiär på Svansjön i koreografi av Rudolf Nurejev gästades Operans Balettklubb av iscensättaren Charles Jude och dansaren Calum Lowden.Charles J...

ANNONS

-

40 år senare: En dansares triumf över tidens utmaningar

-

Fart och kunnande på Pro Dance Galan 2024

-

Svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle har stora framgångar i Berlin

-

Timulak/Portner två olika verk men med flera beröringspunkter

-

På jakt efter det fullkomliga: nationens skickligaste dansare och – smultron!

-

Young Choreographers en föreställning där dansare från Kungliga Operan koreograferar

-

Operans VD Fredrik Lindgren: På sikt vore det fantastiskt att få ett nytt Operahus i Stockholm

-

Från Svenska balettskolan i Göteborg till ungerska Statsoperan i Budapest

-

Joseph Sturdys verk Lucid Episode inleder nyårsgalan på Kungliga Operan

-

Göteborgsoperan sjunger in julen med En Julsaga

-

Nötknäpparen, nypremiär på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm efter fyra års uppehåll

-

Giovanni Bucchieri – en konstnärlig kameleont

-

”Mycket talar för att vi inte kommer att kunna vara kvar där vi är nu,” säger Hans Lindholm Öjmyr, ny chef för Dansmuseet

-

In a heartbeat, ny världspremiär på Göteborgsoperan

-

Le Corsaire, svensk premiär på Kungliga Operan med virtuos dans och teknisk skicklighet

-

New talents join the Royal Swedish Ballet

-

Där låg onekligen ett skimmer över Gustavs dagar

-

Attityder som uppskattades

-

Spot-on Kentaro Mitsumori, dancer with the Royal Swedish Ballet

-

Kalle Wigle-Andersson får stipendium från Jubelfonden

Redaktion

dansportalen@gmail.com

Annonsera

dansportalen@gmail.com

Grundad 1995. Est. 1995

Powered by

SiteVision